Swallowing & Communication (Adults)

This video describes tracheostomy tube cuff management and how we can promote laryngeal rehabilitation.

Most tracheostomy tubes used in intensive care have a cuff inflation port, and a separate sub-glottic suction port. Inflating the cuff seals off the upper airways from the lungs. Any secretions that are aspirated into the airway collect above the inflated cuff, although the seal isn’t perfect. Collected secretions can be removed via the sub glottic suction port. This can be done intermittently or continuously and some systems allow flushing of the subglottic space.

With the cuff inflated, all gas from a ventilator is delivered into the lungs. This allows effective ventilation, especially if high pressures are required, but it means that no gas flows via the upper airways. Without airflow, the patient can’t talk, and without stimulation, the larynx doesn’t work.

We assess laryngeal function using FEES – fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallow. A small camera is passed via the nose to visualise the larynx directly. We can observe function, secretion management, and assess the safety of swallowing by watching how the larynx and pharynx deal with solid or liquid oral intake. After critical illness and tracheostomy, we commonly see secretions pooling in the laryngeal inlet. You can tell that the larynx isn’t sensing the secretions because there is no cough or swallow, and no attempt clear these secretions.

In the video above, there are examples of FEES findings. The laryngeal vestibule is full of thick secretions and there is no cough or attempts to clear secretions. The larynx is insensate and is not functioning.

In order to get the larynx working again, we need to restore some airflow.

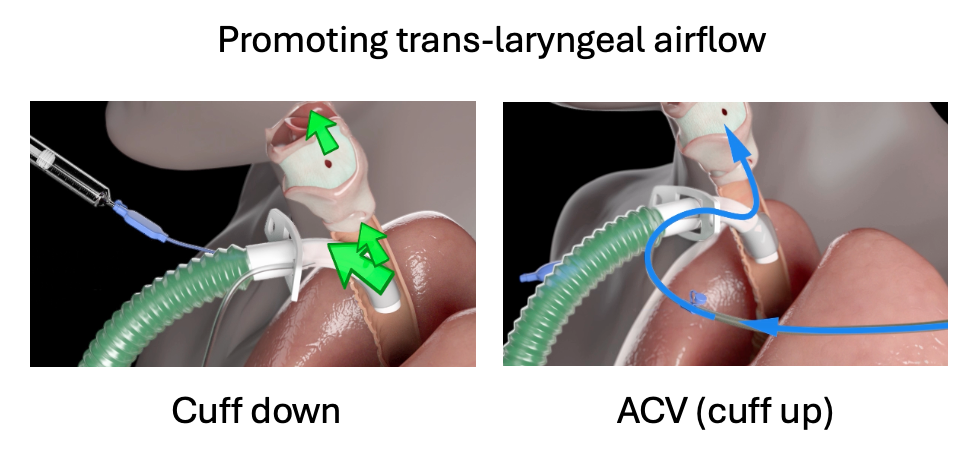

There are two ways of doing this. Firstly, we can deflate the tracheostomy tube cuff. This allows some of the gas delivered to the lungs to escape upwards and out via the upper airways. You need to use a ventilator that will tolerate this leak. The second method is useful when the cuff can’t be deflated – usually because the pressures for ventilation are too high. A flow of gas is delivered via the subglottic suction port independent of lung ventilation, and it exits above the cuff. We call this ACV, or above cuff vocalisation.

With either technique, not all patients get a voice every time, but the gas flow has additional effects. There is a physical effect of blowing any secretions upwards where they are swallowed, coughed or suctioned away. The FEES clip shows us what happens when the larynx switches back on and is sensitive to the secretions which had collected. With a few coughs and swallows, the secretions have all cleared and the vocal cords are visible.

By restoring trans-laryngeal airflow, we are starting the process of laryngeal rehabilitation much earlier in the patient’s journey after tracheostomy. Not only can patients start to talk again, but they can often manage secretions better and work their way back to eating and drinking. This approach may shorten ventilator weaning times, tracheostomy duration, and reduce the chances of pulmonary aspiration because the larynx functions effectively.

Cuff down ventilation, supplemented by ACV where necessary, is part of an effective strategy for early laryngeal rehabilitation.

The NTSP has lots of resources on our website that describe optimal tracheostomy care, including cuff-down weaning strategies and devices to deliver ACV safely and effectively.